Landscapes of Making: Autobiography, Memory and Devised Performance

![]()

Rea Dennis

University of Glamorgan

This paper maps the dramaturgical processes active in the making and performing of Train Tracks & Rooftops (2008, 2009, 2010). A contemporary performance piece produced by Lembrança (UK/Brazil) with the support of the ACW, UK and an Australia/Brazil collaboration, the piece emerged from working extensively within a body memory method of devising that is a practice-as-research approach. Through memory fragments of our own childhood places of refuge, Train Tracks and Rooftops set out to explore how the way in which a child claims self (selves) and place outside the familial, creates meaning and builds identity and emplacement. The paper documents the way in which notions of self are contested when working with autobiography and interrogates how memory is revealed in and through the making process and in performance in a way that suggests autobiography, body memory and improvisation are equal in live performance and compellingly exposing of the performer.

Keywords: autobiography, memory, physical performance, devising

Rea Dennis is an artist and scholar specialising in physical vocabularies for improvised performance and artist/facilitator "performance" in a range of contexts. An international teacher of contemporary performance and applied theatre, she completed a PhD on playback theatre at Griffith University in 2004 and is currently a Reader in Drama and Performance at the University of Glamorgan, UK. She is co-director with Magda Miranda from Brazil of Lembrança, a bilingual ensemble that performs relic-montage of located memory and autobiography using physical and interactive forms.

![]()

In recent years I have been creating contemporary performance from the platform of autobiography, memory and emplacement/placelessness. The convergence of these three conceptual areas opens compelling landscapes for performer and audience alike. This paper interrogates the landscapes encountered during making and performing Train Tracks and Rooftops (2008, 2009, 2010). Through critiquing the making process I question the way childhood memory might lead creative process, how the memory filters and inhibits and how the performer might navigate the different meanings that are uncovered through notions of location, direction and orientation alongside notions of disorientation and alienation.

The making of Train Tracks & Rooftops was conceptualised as an exploration of emplaced memory. Bachelard writes about memory spaces and how they are located or emplaced. He emphasises the way in which our first house “plays a significant role in the forming and sustaining of memory.” He champions the material home as a “site within which one’s imagination and day-dreaming can take place and be given free rein.”2 Bachelard’s focus on the child at home overlooks the possibility that for some children, it is those places outside of the home where they experience the sensation/state of being sheltered. In an extension of the themes of migration, alienation and identity in my earlier Performance as Research, Apart of and A Part From, Train Tracks and Rooftops set out to explore ideas of refuge from the point of view of childhood memories. The original Arts Council of Wales funding application stated that the project sought to explore “childhood memory of place and the search for emplacement beyond the materiality of home and family [drawing] on images and objects from the city of São Paulo (Brazil) [and] a beach in Australia.”

In 2008 I began working with Magda Miranda as Lembrança (Brazil/UK)3 and this was our first project. The locations identified are personally relevant to Magda and I and were selected because they had begun to feature in the personal exchanges between the two of us at the time as we sought to paint pictures of our cultural emplacement for each other. She, a Brazilian, would recount stories of a high brick dividing-wall (The Wall) that ran alongside her place. As a child she would climb up the wall and ease her way along the top of it to access the tiled roof of her home. The wall and the roof were dominant features in her childhood back yard in inner city São Paulo when she was about 7 years old. With a similar passion and childlike earnestness I, an Australian, shared memories from episodes at Pottsville beach (my childhood beach in Northern NSW) from when I was around the same age. As we shared these located memories there was a sense that we were anchoring ourselves in a familiar cultural narrative while at the same time being invited to experience the unfamiliar sounds, sights and textures of the other’s place. The quality of these exchanges informed the project and became points of departure for improvisational experimentation and devising. The stories we shared and those memories associated with, located in, and uncovered during improvisations, became the geography of a collaborative journey.

Landscapes of Making: Memory and Autobiography

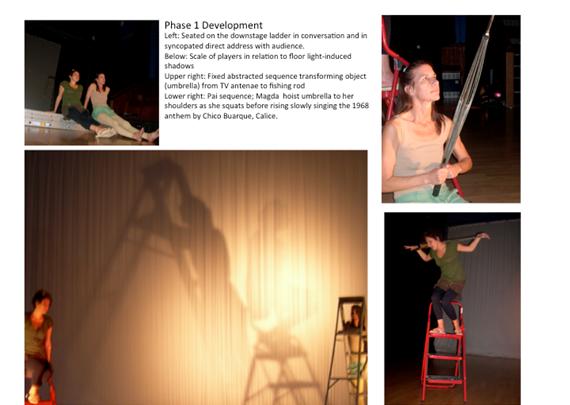

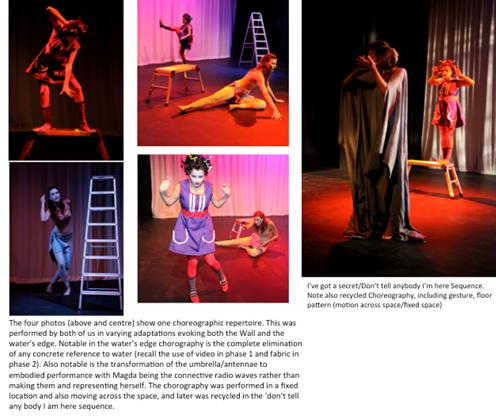

From the outset, the exploration of memory fragments of childhood places of refuge, made Train Tracks and Rooftops resonant with notions of identity, place, and belonging. After de Certeau, our stories; those narratives we construct about our lives, reveal that we are engaged in mapping and re-mapping our identities. Telling stories is a way we make meaning of our lives, of ourselves, of others, and of the world we live in. Contemporary autobiographical performance has emerged as a methodology of making or devising in which “the use of personal interests and narratives as source material leads to a complex creative process that reflects upon real life data to shape a performance piece.”4 In developing Train Tracks and Rooftops, we underwent three phases. The initial phase sought to liberate these places and our initial memories as performative. This phase drew on the established performativity of the two performers and could be said to have adopted Deidre Heddon's loose description of autobiographical performance, relying on the direct address mode in which performers engage immediately with audience members through performed storytelling. In this phase the style drew on narrative storytelling structures and fixed locations in the space: a roof top, the ocean, a wall on which we sat and recounted stories, and also narrated transitions in each others' solo sequences. Four ladders of vary sizes together with an umbrella were incorporated in a range of ways to support the work. In some respects we were performing two discrete solos simultaneously. The composite below, Figure 1, gives some insight into the simple design, demonstrating the way in which we sit to directly address the audience in the opening sequence, which occurred after a percussive music score made by slapping rubber thongs together.5 Then larger of the images in Figure 1 attempts to reveal the space and spatial relationship between the two principle ladders and the way lighting design was integrated to incorporate shadow work.

FIGURE 1: Train Tracks and Rooftops Phase 1

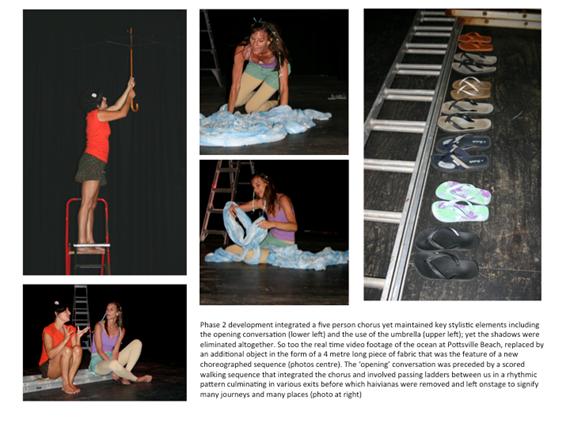

In Phase Two of the research progressed with a narrowing of the line of inquiry. This phase was awarded a development grant for the express purposes of translating the traditional storytelling mode to a non-narrative mode that drew on sonic, kinaesthetic and visual languages. The research focus was to disrupt the organising dominance of narrative as a dramaturgical structure and shift to the structural elements of time and space. Back in the studio we entered somewhat of a deconstruction phase in which the components of phase 1 were pulled apart and reconsidered in a range of improvisations and experiments. Figure 2 shows the way the design has altered as the adaptation of the narrative form progresses.

Narrative is a dominant organising structure situated within our innate cognitive processes and is ever active as we live the day-to-day, as we move around in the world, experience, perceive and respond to the world around us. Yet while constructing stories - translating experience into stories - is innate, stories do not exist only in verbal form. Neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio explains: “Language - this is, words and sentences - is a translation of something else, a conversation from nonlinguistic images which stand for entities, events, relationships, inferences […] symbolising in words and sentences what exists first in a nonverbal form.”6 It is the idea of performance as non-verbal storytelling that framed the project: the domain of perception, where senses, rather than cognition lead the making.

The idea of shifting away from the cognitive mapping through narrative toward became a principle navigational marker within the research. Our task was to establish conditions to support our access to pre-expressive or nonverbal story structures from our memories. Four areas, that is, four conceptual/contextual threads, were active at this stage of the inquiry:

- Memory fragments (childhood places of refuge) as stimulus for devising from autobiography;

- Emergent memories as navigational guides; including vagaries of memory – real, assumed, narrative, sensual, cognitive;

- Translation of autobiography away from the dominance of narrative organising structures through improvisation within physical and visual languages;

- Practices of collaboration that feature improvisation with a co-performer/deviser and with audience members.

FIGURE 2: Train Tracks and Rooftops Phase 2

Writing on autobiographical performance, Govan Nicholson and Normington suggest “the exploration of identity […] is often at the heart of autobiographical performance.”7 Yet, with the co-ordinates of the piece being tied to real locations, to the specificity of the places - Pottsville beach and the Tatuápe rooftop - it was our memories, and the conscious and unconscious stories we had constructed over 30 years to hold, maintain and conserve these places as perfect in some way that was the source material. The way we remembered these places was about to come under a scrutiny that would disturb their place and meaning in our memories and in so doing, disturb our identities.

So, what was it we were drawing on to stimulate devising? Damasio provides a useful conceptualisation of autobiographical memory as:

an aggregate of dispositional records of who we have been physically and who we have usually been behaviorally, along with records of who we plan to be in the future. We can enlarge this aggregate memory and refashion it as we go through a lifetime. […] The real marvel as I see it is, that autobiographical memory is architecturally connected, neutrally and cognitively speaking, to the non-conscious proto-self and to the emergent and conscious core self of each lived instant [… thus while] the basis for the autobiographical self is stable and invariant, its scope changes continuously as a result of experience.8

Some eight months after phase 2 we re-entered the studio for a third phase of development. Our focus on autobiographical memory for content and the application of the navigational focus to disrupt narrative structuring resulted in slippery terrain for the performer/auteur. The following section examines the artists’ experiences of dislocation and alienation in a making process and explores the way in which form became content as the language of physical performance developed and the way that the process induced a kind of confrontation of personal memories and the truths we had told to ourselves.

Crumbling Architectures: Dislocation and Alienation

The places selected for the points of departure in this work are places the artists have identified as havens, loved places, places of refuge; usually occupied alone, without censorship or witnesses. Bringing these locations into the studio resulted in a different experience. Magda Miranda reflects:

Regardless of what I was conscious of bringing, and you too for that matter; we brought our stories and feelings. They all came alive … there were also things that came alive that even when I didn’t want to acknowledge their presences, somehow I could not refuse – but sometimes I did.9

Deirdre Heddon claims “creating [an] autobiographical show means literally creating part of yourself.”10 Implicit in Heddon’s note is that this creative act is positive and perhaps even celebratory. Autobiographical performance has a tendency to enable the performer to present themselves and to explain or reveal those aspects of their identity that has driven and motivated the work. There is less written on the way in which autobiographical work calls forth selves that may be unfamiliar, and indeed even unwelcome. Viv Gardner offers some thinking about the clash of selves that can occur in the dramaturgical layering that is active when performing self and other active identities are circling one another and seek to coexist. “Unpicking the ‘inner life’ - or even the ‘real life’ - from the complex matrix that informs and defines the performers autobiography is no simple task”.11 During one rehearsal I experienced a moment of deep doubt about what elements of me might dislodge and what selves might come tumbling out. Magda reflects:

I remember when we were working to find your story with the ocean and you just started to find other people’s stories. You even said, ‘I don't want to talk about my brothers’ or something like that, for me it seemed that there were memories coming and you were afraid and were trying to protect yourself.12

In the rehearsal that Magda is referring we were working on choreography linked to the ocean motif. We had discovered a range of elements and identified textures and shapes but were dissatisfied. There appeared to be no vitality in me. As director, Magda made suggestions and eventually shifted on stage working in duet with me, adopting antagonist positions within the scenarios, working to shift the energy (of me/the piece). A sequence developed around my vocal expression of the word ‘No;’ while the movement was confrontational and physical. In the moments of contact and space between the two bodies I felt other memories from that period, nothing tangible - visual or narrative; it was more in terms of attitudes and in some cases, sensations. More obvious was my awareness of a deep resistance to continuing with the sequence, mirroring the ‘No’ text that I had been reciting. The simultaneous landscapes of the piece we were making and the process we were undertaking converged for me in a way that I was unable to understand. Later in reflection I wrote: “Working up to the ‘No’ sequence, I can really see three discretely different fights in me.”

I was saying No to my mother. I realised I was remembering her at that time as the one who denied me my voice, the one who blocked my freedom, my spontaneity, my independence.

I was saying No to Magda, to her pushing me to follow this vein of memory, acting on the one hand as my mother in a provocation improvisation, and on the other hand as director. My “No” grew stronger.

The third No was to the exposure – I did not want to go there, to feel the powerlessness, the invisibility and impotence associated with my pre-pubescent years when I was without the liberty to make my own decisions. This No was also linked to a kind of humiliation I felt during winter at the beach that I cannot fully understand but that emerged in later improvisations as the don’t tell anybody I am here/ I’ve got a secret sequence.

In the final composition, the don’t tell anybody I am here/I’ve got a secret sequence held important identity markers, emerging from a place of childhood autonomy and empowerment. In hindsight I wondered if the resistance I felt was the memory of resisting telling anybody where I was during those times as a child that I fled to the beach. Discovering the sequence was very revealing for both of us as we came to understand that we both had the belief that our ‘places’ only held sanctuary when we believed that no one knew where we were, when there was no risk of being witnessed, supervised, judged, or ‘seen.’

Ironically, as adults, the ‘place’ of performance had also manifest as a safe place for both of us. It is the disorientation we experienced in relation to this place and to our identities as performers that I will consider next. Our working process was rigorous and set out to explore new terrain for both artists after years of success as soloists within our own established forms.13 Adopting a line of inquiry that focused (somewhat ruthlessly) on disrupting the dominance of narrative as an organising structure disrupted more than our perceptions of the moments. As Magda states:

Train Tracks and Rooftops started with a story about me [sic] trying to find myself when I was 6 or 7. My place. And this place (rooftop) is deeply linked to my [early experiences of] not belonging, my fears, my loneliness and low self esteem. At times when you [Rea] directed me or in those moments when I felt I could not do anything, the feelings - Magda from the past and Magda the performer¾mixed.

The terrain of autobiographical performance situates the performer in a confrontational relationship to themselves where the “selfhood of the performer is foregrounded as [we] seek to represent [ourselves].”14 Yet at the same time we are not trying to represent ourselves we are being ourselves and as such are “framing the everyday in a manner which reflects upon the constitution of identity itself.” 5 Magda refers to the real and the symbolic meaning of her ‘roof;’ a place where she could ‘find herself’ far from feelings of ‘fear,’ ‘loneliness’ and ‘low self esteem.’ While we were consciously engaging with unknown territory, the challenge came from the way in which the making experience appeared to be creating tensions in direct contradiction to the conceptual markers of the piece: refuge, freedom, and personal safety. In our discussions sometime later we acknowledged that we both experienced a kind of fear; like something was about the break. We were lost to ourselves. Magda’s journal notes state: “The fear of not being able to communicate haunted me. I truly believed the audience would never understand the piece.” Frustrated at what she felt was her failure as a performer and the failure of the collaboration, she began to ‘unpick’16 her idea of herself as an artist:

The difficulties we found […] were so intense that I started to question my work as an actress. It was in this process that I got quite a shock to realise that although I had devoted eleven years of my life to dance, I had completely forgotten about my body. I met the limitations of my movements and a lack of flexibility.I left several rehearsals physically and emotionally destroyed and wanting to give up.17

Uncertain Destinations: Navigating the Unfamiliar

In some respects this phenomenological struggle we found ourselves in could be written off as a fairly rudimentary step in creative practice. John-Steiner reflects “marginality, estrangement, and self doubt frequently plague creative people.”18 John Freeman19 examines the phenomenon of dislocation in respect to performance as the place in which we encounter the acute sense of cultural displacement that is a common experience for people today. The making process appeared to have arrested the zone of safety that the ocean and rooftop had represented to the child-Rea and the child-Magda and we began to lose faith in the piece. In reflection, we found that the specifics of the narrative fragments guiding us had begun to appear in our reflective notes and discussions as the adjectives to describe our sense of failure and disconnection. For example I write: “we are all at sea;”20 drawing on the located centre of my narrative as a metaphor to explain my sense of dislocation. At around the same time Magda states: “It was then that encountered with a big new wall – Myself;”21 drawing on her locale as a synonym for being blocked or oppressed. In both utterances there is reference to the locations: the sea; the wall; as places of entrapment, or barriers to expressivity, rather that the constructs of freedom or liberty that the locations had represented to the child-Rea and the child-Magda in their memories. The process of devising had begun to undo the memories as discrete narratives and in so doing, unravel our identities as performers… it was as if the children were at risk of losing their pasts.

The landscape of devising was proving challenging and whilst the maps of our memories were worn, our contemporary selves were resisting the way in which the present experience was mixing with and disturbing the narrative fragments and as such sabotaging our creative confidence. I note:

There is some kind of fight happening; between our creative intention and our inner resistance? The work is imploding. […] I have to surrender. My vision of becoming conversant with the weight and fall of the ladders is beyond us. We seem to be clinging to these physical objects like life rafts as we are washed off our certainty and flung into moments of memory through the techniques that served to aggravate the emotional experience that the very starting locations (beach, roof) promised to protect us from. The focus on translating the narrative seems to be subverting the experience of refuge and maximising the experience of alienation and terror.22

Williams speaks about this kind of lost state that the deviser encounters as “creative blindness” and says that the performer will move into and out of this as they engage “in a dynamic process of dramaturgy.” He writes:

Performers in devising contexts are active makers, composers. So they need to be engaged physically, imaginatively, intellectually, in thinking through processes of exploring and translating ideas, materials, scores, structures, images, rhythms, and relations. In other words, they are doing ongoing dramaturgical work that is then developed, layered, placed in other relations.23

The kind of locating that the performer experiences in this dramaturgical process offers essential landmarks and can also provide road stops on a journey characterised by uncertainty. For us, uncertainty was not unfamiliar; however having this uncertainty unpick the fabric of our memories created significant disruption to our identity markers. Working with piece of physical theatre it is always the physical drills that I seek as the base in ensemble building and collaboration. Yet, my confidence in myself as a practitioner and in the working relationship with Magda plummeted when I experienced my incapacity to facilitate the combining or coalescing of our working styles into a shared vocabulary. Despite experience in our own individual practice processes - on tacit strategies and procedures - things that had previously worked for us as soloists, we faltered. At the time we seriously began to (re) consider the value of the work for an audience.

Barry Le Va identifies moments where artists must adjust their perceptions and expectations:

What it does, for me, is that it destroys, at a certain point, what I was interested in - any sense of correct judgment, any sense of stableness. It doesn’t produce confusion, but it does set up a situation where one has to question one’s own thought process. The situation becomes active, organic; it grows and seems to be in a state of flux due to the constant re-adjustment and re-evaluation of your perceptions […] All of a sudden things are being subverted and you realise that the work wasn’t about what you first thought.24

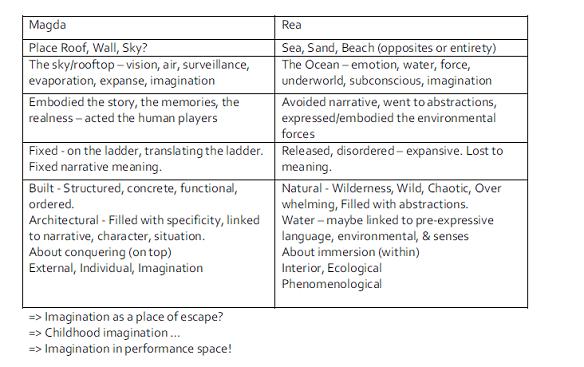

This processes of adjustment occurred in two discrete steps. As we questioned our ‘thought processes’ we focused on observing what was actually happening rather than what we thought should be happening. The simple question: What is this piece? Enabled us to remap the conceptual terrain and to reposition some of the navigational markers. Our notes reveal the following kinds of juxtapositions:25

FIGURE 3: Train Tracks and Rooftops Juxtapositions

At this point it felt as though we had arrived somewhere. The conceptual terrain of imagination opened a rich area of content to explore and compelled the making process forward. Perhaps it is not surprising at all that we arrived here. UK contemporary performer, Alexander Kelly speaks about the process of making autobiographical performance, as beyond cognitive understanding much of the time. It “strays into the grey area between … memory and imagination.”26 David Williams suggests that “there are multiple strata and stages of dramaturgical work in devising contexts.”27 Through this phase, a critical shift in our perspective saw rapidly redraft the rehearsal room critique from a social to aesthetic reading. Key elements of the earlier versions of the piece were transformed and vibrant visual piece emerged based on a vocabulary of shape, rhythm, colour, gesture and image. See Figures 4 and 5 for some indication.

FIGURE 4: Train Tracks and Rooftops Visual Vocabulary

FIGURE 5: Train Tracks and Rooftops Visual Vocabulary

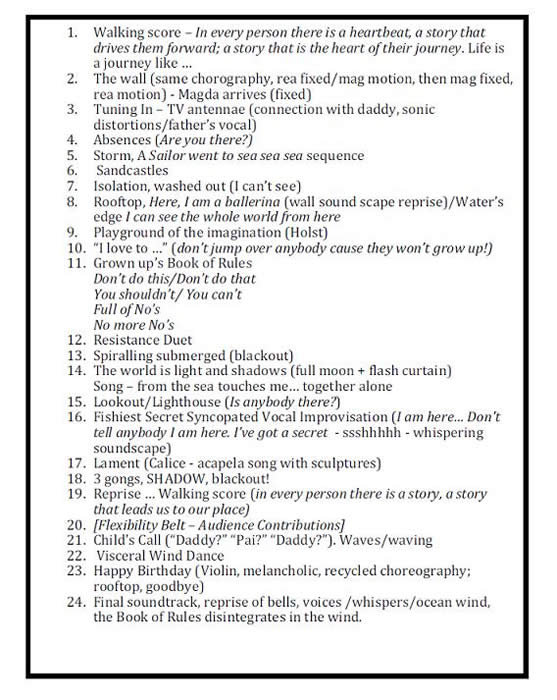

Memory spaces and working toward nonverbal narratives opened uncharted spaces within our collaboration. Considering these kinds of ambiguities from an embodied perspective Weiss argues that in “acknowledging and addressing the multiple corporeal exchanges that continually take place … demands a corresponding recognition of the ongoing construction and reconstruction of our bodies and body images.”28 Using strategies to minimise the self-censorship enabling us to continually engage in encounters with (our) self, each other, and the absences that we found unfamiliar considering our lengthy experience with improvisation and performing. We also altered the way in which we were thinking in relation to shaping the audience experience seeking to trust a more loosely held dramaturgy in where spectators interpret and draw meaning from experience rather than narrative. Revisiting the essential narrative framing “a place of refuge” we were again able to ask: refuge from what? This released a range of creative threads including the issue of the child’s perspective, which led to a reconsideration of context. These trails led to the more epic style of the piece and shift in the values informing design and use of space and objects in order to create environments on stage. The style of the work began to resemble a more ritualised physical theatre form. See Box 1 below for the way the piece was assembled.

FIGURE 6: Train Tracks and Rooftops Scores & Sequences List

The work began to open more toward the audience and move away from a performer-centred thinking. Writing about physical theatre more generally, Dymphna Callery recognises that the collaborative nature of the devising process extends to the reception process and suggests that, “the stage-spectator relationship is open.”29

From the spectators’ point of view physical theatre accentuates the audience’s imaginative involvement and engagement with what is taking place on stage. There is greater emphasis in exploiting the power of suggestion; environments and worlds are created on stage by actors and design elements provoke the imaginations of the spectators, rather than furnishing the stage with literal replications of life.30

Co-existence: Collaboration, Territories and Borders

From a distance, one could argue that theatre-making enacts a kind of homage to collaboration. Collaboration is implicated as a central component of the process and might refer to aspects of communication between artists, creative collisions; a space for magic to happen. Vera John-Steiner states “collaboration offers partners an opportunity to transcend their individuality and to overcome limitations of habit and of biological and temporal constraints.”31 Such claims tend to focus on the result or the outcome and lack the colour of lived experience. Theatre artist Tim Etchells on the other hand suggests something entirely different stating that collaboration is not “a kind of a perfect understanding of the other bloke, but a mis-seeing, a mis-hearing, a deliberate lack of unity.”32

The experience of Train Tracks & Rooftops proved to be an experience of unraveling identity in such a way that reinforced our individuality. The more we constructed our working process as collaboration in Steiner’s sense, the more the creative process faltered or seemed to be failing, and the further away from each other we appeared to be. Somewhere in the middle of the project there appeared to be no capacity to communicate, no shared vision, shared method, shared content, or shared decision-making process. In some respects, what occurred between Magda and I could be interpreted as the “lack of unity” that Etchells refers to, however it was not consciously deliberate. The effort to shift the critical gaze from interpreting the collaboration as problematic toward a reading of the process as aesthetic enabled us to continue. Indeed, in Etchells practice reflection he goes on to state that the features of collaboration, this mis-seeing, mis-hearing and absence of unity, find “its echo in the work, since on-stage what we see is not all one thing either – but rather a collision of fragments that don’t quite belong, fragments that mis-see and mis-hear each other.”33

After each performance of Train Tracks & Rooftops there was a tangible sense that audience and performer were both present as participants in something. In our aim to disrupt the narrative telling of these memories about places that represented refuge to us as children, a space opened so that the performance itself began to exist as a “place” for performer and audience alike. One audience member reported:

This show was very powerful. Different elements reminded me of Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, childhood trips to the beach, that sense of home that never leaves us and also a sense of adventure that unfortunately as adults we seem to forget … a moving uniqueness that made for a highly provocative experience.34

Gil’s comment suggests that despite the experience we had in the devising, she was free to embody her own personal version of the performance. She entered the worlds in the performance with a high degree of autonomy and brought many aspects of herself to bear on her reading. She has brought things from other places into the room, in some respects she can be thought of in terms of Ranciere’s “emancipated spectator.” 35 Ranciere establishes an innate reciprocity between audience and performer beyond understanding. He claims that there is a naturally occurring phenomenon of human interaction where interpretation rather than understanding is privileged. Audience members are “active interpreters who try to invest their own translations in order to appropriate the story for themselves and make their own story out of it”.

Etchells’ stance, that collaboration occurs beyond understanding, similarly emancipates the artists, liberating us from a preoccupation with cognitive meaning making and situating the negotiation of meaning in relationships - performer and audience, performer and performer, performer and self, audience and self. As the narrative storytelling elements diminished throughout the various phases of Train Tracks and Rooftops, the way in which the audience read the performers and the performance seemed to expose the performers more, and render their real relationship more real, illuminating their vulnerabilities and limitations. Just as the performance was built moment-by-moment, so to, participant experiences are built moment-by-moment and are composed of the complex intersection of the various elements of the performance: words and sounds - what is said and what they hear, movement and pictures - what they do and what they see, interactions, responses, and reflections. Ilisa’s engagement was visceral; she wants to be closer, to enter the states on stage, to be with us:

There was a sense of vastness, distance and life journeys/transitions - flowing, sometimes disjunctive with characters in different places. Wanted to be closer to you - in it - walking/tracing my own path.36

Yet another audience member alludes to boundaries and engages with the piece as many places:

There is a complex narrative structure, the story shifts fluidly from place to place so that at times the audience is not sure whose story they are supposed to be watching. Form and narrative merge through the merging between locations, and offers (beyond representation) the phenomenological experience that our space may not be defined by our nationality - from where we come. Rea and Magda allowing their stories to collide, move in and out of each other and the deliberate invasion of space is an artistic commentary on how the whole concept of borders, and nations and ownership of space stops us from being able to see what it is we share at our most human.37

The work of Train Tracks and Rooftops purposefully privileges the multiplicity and inconsistency of memory where, unlike for example Mike Pearson who “set out to uncover records and photographs of me in this place, to discover physical marks I left in the landscape, in order to re-embody the traces the landscape has left in me: to relocate myself”38 for his Bubbling Tom work, Train Tracks and Rooftops explores the way in which these places and the ages we were when we occupied them were inscribe on an inner landscape; one of embodied memory. Yet, like Pearson who claims an acute awareness of the vagaries of remembering and sensibility to the ‘liveness’ of place, to its ability to morph, the work is occupied by gaps and incompleteness and might be considered a kind of temporary ‘autotopography’ in which our childhood memories might intersect and influence each other and where our different methodological approaches and performance styles are present, without coherence and unity.

I leave the journey here at this point in time in the hope that your engagement with this series of fragments and the way in which I have mapped the journey has some resonance. The writing endeavours to document a collaborative working process, various lived experience, all recreated from memory. In the making of Train Tracks and Rooftops we travel to each other’s country of birth and subtle nuances that characterised the work were developed along the way. Through engaging with our own and each others’ memories, methodological traces, motifs, structural devices like ladders, light and sound, and disrupting individual performer repertoires, the process led us to very difficult terrain with intense creative challenges and resulted in the development of a piece of theatre that was beyond both our previous experiences and also beyond what we could cognitively have conceived individually. The notions of childhood and imagination became the central drivers in the investigation. The continuous unfolding and refolding of the map has revealed a strongly structured consideration of the themes of entrapment and freedom, safety and risk, awareness and naiveté, solitude, existence and loneliness. The piece became a “place” for the performer and for the audience. The experience of watching/participating seemed to open specific and personal points of connection for different audience members. In trying to understand the aesthetic emerging from this working process, it seems that the practice is mirrored in the content of the piece. The journey engaged with our autobiographical aggregates; those “dispositional records of who we have been physically and who we have usually been behaviorally” and in doing so the memories we unpacked of places in which we were empowered agents of our own destiny are “refashioned” in Damasio’s39 terms; the architecture, cognitively and neurally speaking, has changed. We are changed through this encounter our adult selves, interrogating the fixed points of the narrative memory, and destabilising our sensory and emotional memories. The creative act of making and performing remapped parts of our identities. The collaboration was a fierce voyage. In some respects we were constantly fighting with ourselves, our pasts, our memories, our ideas of our memories; and pushing the other away from our private business.

NOTES

- 1 Gaston Bachelard 1995:201 cited in John Urry, Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century (London: Routledge, 2000) 117.

- Ibid, 117.

- Lembrança’s remit is intercultural (Brazil/Australia) collaborative co-solo contemporary performance created through the engagement with and transformation of relics, mementos and artefacts of memory.

- Emma Govan, Helen Nicholson and Katie Normington. Making a Performance (London: Palgrave, 2007): 60.

- Popular in Australia in the 60s and 70s, these rubber thongs, called Haiavianas in Brazil, were iconic in both our childhoods and were selected after experimenting with objects.

- Antonio Damasio, The Feeling of what Happens (London: Vintage, 2000) 107-108.

- Emma Govan, Helen Nicholson and Katie Normington, 66.

- Ibid: 173.

- Magda Miranda, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- Deidre Heddon, Autobiographical Performance (London: Palgrave, 2007): 18.

- Viv Gardner, The Three Nobodies: Autobiographical Strategies in the work of Alma Elleslie, Kitty Manon and Ina Rozant. In Maggie Gale and Vivien Gardner Auto/biography and Identity: Women, Theatre, and Performance. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004) :11

- Magda Miranda, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- In some respects it was more ‘new’ for Magda as she agreed to work within my Practice-as-Research project, that is, these research questions had arisen from my previous PaR project.

- Emma Govan, Helen Nicholson and Katie Normington. Making a Performance (London: Palgrave, 2007): 59

- Ibid: 60

- Viv Gardner, 11

- Magda Miranda, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- Vera John-Steiner, Creative Colaboration (NY: Routledge, 2000) 126.

- John Freeman, New Performance Writing (London: Palgrave, 2007) 62.

- Rea Dennis, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- Magda Miranda, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- Rea Dennis, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- David Williams, ‘Geographies of Requiredness: Notes on the Dramaturg in Collaborative Devising’, Contemporary Theatre Review 20.2 (2010): 198.

- Barry Le Va, ‘In interview’, in Nick Kaye ed., Theatre into Art: Performance Interviews and Documents (The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Press, 1996) 53.

- Rea Dennis, Practice Journal (unpublished, 2008-2010).

- Alexander Kelly, 2000:49, cited in Emma Govan, Helen Nicholson and Katie Normington 62

- David Williams198.

- Gail Weiss, Body Images: Embodiment As Intercorporeality. (New York: Routledge, 2003) 76.

- Dymphna Callery, Through the Body (London: Nick Hern Books, 2001) 4.

- ibid, 5.

- Vera John-Steiner, 57.

- Tim Etchells, Certain Fragments (London: Routledge, 1999) 56

- Ibid, 56.

- Audience interview, Gil, Cardiff, 27/1/10

- Jacques Ranciere, The emancipated spectator (London: Verso, 2009), 11.

- Audience interview, Ilisa, Cardiff, 23/1/10

- Audience interview, Hasta, New York, 05/10/2008

- Mike Pearson, ‘Bubbling Tom’, in Adrian Heathfield ed., Small Acts: Performance, the Millennium and the Marking of Time, (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2000) 175.

- Antonio Damasio, 173.