Mapping the Performative Geography of a Latter Day 'Happening'

Paul Davies

University of Queensland

On the 26th of November 2009, outside the Brisbane Convention Centre, an intercalation of three distinct social spaces took place: a ‘real demonstration’, a ‘mock press conference’ and the ‘annual general meeting’ of one of the world’s largest mining companies. This paper examines the creation and management of performance space in that ‘mock press conference’. Sir Don v. The Ratpack was a form of contemporary agit-prop theatre, effectively a latter day ‘Happening’, produced by Mullumbimby’s Gorilla Street Theatre (GST) troupe to highlight the huge expansion of uranium mining about to take place at Roxby Downs in South Australia. I argue that the ‘energy’ embodied in Sir Don’s polarised contest between actor/journalists seeking answers on the one hand and the pretend company chairman denying everything on the other, creates a commonly understood space of performance: the door stop press conference – effectively a mobile heterotopia. As with much site-specific practice, Sir Don is authentic, transgressive and permeable, unlocking new ways of experiencing a performance and new orders of relationship between actor/participants and spectator/onlookers. It is brought into being and sustained as an integral space simply by pointing cameras and microphones towards a concentrated spot (the subject – Sir Don) and asking him questions. It also unfolds in real time, and like the democratic circle around a fight, the shape of its formation of spectatorship (and participation) can bend and extend, thicken and reform. Sir Don even manages to insert itself into the heterotopia of BHP’s AGM. Equally, it draws in the social space of the nearby “International Convergence” a real/traditional demonstration otherwise kept at a distance by the strong police presence. Thus, this latter day Happening deploys itself as a third, liminal performative space which mediates the divide between both places of antagonism: company and protesters – effectively bringing itself, as part of the larger demonstration, into the realm of the exclusive corporate gathering.

Keywords: Site-Specific Performance, Location Plays, Heterotopia

Paul Davies graduated from the University of Queensland in 1972 with a BA (hons) and MA in English Literature. He also trained as a script editor at Crawford Productions where he arrived in 1974 in time to witness the killing of Homicide and the birth of many Sullivans. Paul has written for more than a dozen television drama series including Homicide, The Sullivans, The Box, Skyways, Stingers, Pacific Drive, Rafferty’s Rules, Blue Heelers, Headland and Something In The Air. He has also co-written a number of documentaries for the ABC and SBS with directors John Hughes, Pat Laughren and Rosie Jones. Two plays, Storming St. Kilda By Tram (1988 Currency Press) and On Shifting Sandshoes(1988) received Awgies (Australian Writers Guild Awards) as did Return Of The Prodigal an episode of Something In the Air. The original ‘Tram Show’, Storming Mont Albert By Tram, was first produced by TheatreWorks in 1982 and performed on many trams over the next decade in both Melbourne and Adelaide, helping to pave the way for other site-specific plays, including: Breaking Up In Balwyn (1983), Living Rooms (1986), and Full House/No Vacancies (1989). Paul has also lectured in screenwriting and media studies at various universities and tertiary institutions. He is currently a PhD candidate in the school of English, Media Studies and Art History at the University of Queensland.

![]()

Sir Don v. The Ratpack (2009) was designed by Mullumbimby’s Gorilla Street Theatre troupe to draw attention to the huge expansion of uranium mining about to be undertaken by BHP Billiton at Roxby Downs in South Australia. A form of agit-prop theatre it was mounted outside the Brisbane Convention Centre on the 26th of November 2009 to coincide with the company’s Annual General Meeting - part of an ‘International Convergence’ of protestors from around the world. Sir Don also worked as an item of performance research for a project examining TheatreWorks’ self-styled ‘location plays’ of the 1980s. I hoped to co-opt the event, and its enduring presence on the internet, as one way of demonstrating what happens when various social spaces, such as those created by a site-specific performance, collides with, or in this case, surreptitiously inserts itself - like Boal’s ‘invisible theatre’ - into the place in which it unfolds.2

Theatreworks’ location plays took place on trams and river boats, in pubs, gardens and houses and their popular appeal lead to a breakout of site-specific practice in Melbourne throughout the 1980s. My basic proposal, drawn from this suite of productions, is that when the narrative space of a play with its characters and their backstories unfolds in a place authentically related to that particular story, a new set of interconnectivities becomes possible; not only between actors and audience, and within the audience itself, but between both and a larger outside world in which the production unfolds. I argue that this is something that offers a fertile way forward for theatre, and along with associated factors such as the engagement of senses beyond sight and hearing, delivers a experience that no form of sight-specific theatre can match, let alone any screen or digital reproduction - no matter how allegedly three dimensional it may claim to be. Thus, audiences for Storming Mont Albert By Tram were fellow passenger/commuters with the characters as the story took place all around them, both on and off the tram, so that both parties moved and interacted as a community-of-the-show with the streetscape of a suburban tram route. Here the audience could watch, framed by their own reflections in a tram’s window, the interaction of departing characters with the random events and reactions of the ‘real world’ going past outside.

Site-specific Performance Space and Heterotopia

One way of reading the complex spatial interplay that is going on here – the creation and management of these separate topographies - places and spaces - is to deploy Lefebvre’s understanding of how social space is produced “by the energy deployed within it.”3 Drawing on Fred Hoyle’s astrophysical theories, Lefebvre demonstrates how non-physical space may be produced in what he calls ‘representational spaces’ which “overlay physical space making symbolic use of its objects.”4 This aligns with Michel Foucault’s (and later Kevin Hetherington’s) notion of the heterotopia as a place of ‘alternate ordering,’ which Foucault introduced in a lecture in 1968 in order to describe certain “counter sites”: places of contested and simultaneous representation.5 For Hetherington the key point about heterotopia lies in the relationship between such spaces, the various oppositional factors that they throw up as “sites of alternate ordering.”6

Heterotopia are sites in which all things displaced, marginal, rejected or ambivalent are represented and this representation becomes the basis of an alternate mode of ordering that has the effect of offering a contrast to the dominant representations of social order. There is nothing intrinsic about a particular space that might lead us to call it a heterotopia, rather heterotopic relations are produced in the relationship between sites that have come to stand for different forms of social ordering and representation.7

In other words, heterotopia are established “through the juxtaposition of things not usually found together and the confusion that the resulting representations creates.”8 Appropriately for an embodied art form like theatre, the word ‘heterotopia’ itself derives from medical usage, originally referring to parts of the body that are missing or in the wrong place.9 In an echo of Lefebvre’s point about space being produced by the energy deployed within it, Michel de Certeau describes how “ the street geometrically defined by urban planning is transformed into space by walkers.”10 It follows that by occupying the space outside Brisbane’s Convention Centre “like walkers,” GST’s actors could thereby not only occupy but transform it, the key to which lay in movement (walking).

One way to achieve mobility at the planned International Convergence was to constitute a mock door-stop press conference outside the AGM, allowing GST to raise the relevant environmental and social issues (as ‘journalists’) and to move all over the steps in any direction dictated by the central interviewee: the actor playing ‘Sir Don’. After all, mobility as a common element of site-specific performance also arrives, among other things, from its derivation in political street theatre and the consequent need to keep pace with a larger (often moving) demonstration, to minimise arrest essentially - to move on, but keep performing.

Heterotopia of the door stop press conference

The convention of the door-stop press conference, so familiar from the nightly news, is essentially that of an improvised (non-matrixed)11 contest between a random assemblage of journalists and paparazzi with their various notebooks and digital recorders on the one hand, and the person they’re seeking answers from on the other – the latter sometimes flanked by minders, security, police, lawyers etc. The heterotopia of this performative circle, the social space of a common media discourse, is ‘created’ in the Lefebvrian sense, largely by the act of journalists pointing cameras, questions and other recording devices in the direction of the celebrity, politician, authority, or person of current public interest being pursued. Sometimes these ‘targets’ attempt to hide their identity and avoid the media, in other cases they are happy to promote their own take on events and bask as it were, in the limelight of such frantic attention. Like Lefebvre and de Certeau, Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks agree that “events create spaces.”12 In this case, the ‘democratic circle’ is something they observe forming around a fight in public. Such a circle is key to understanding the mechanics of any space of contest, with the proviso that in the mobile press conference scenario, there is generally a single combatant on one side (answering/avoiding questions) and any number of media players (opponents) on the other, throwing the questions out. The live ‘audience’ for this ‘fight’ (the media pack) is, in a very direct sense also deeply implicated as one of the combatants (setting aside the intended audience witnessing these events via the subsequent media and print broadcasts). In most examples of the ‘door-stop’ press conference, there is an underlying assumption that the journalists are seeking the truth (or some further complication of the public narrative, a denial, exposure, or trip-up etc.); while the targeted subject attempts to subvert the truth or at best avoid making an embarrassing public mistake. Whether this is correct or not, the basic combative nature of the press conference trope (and its underlying transparent mendacity), gives it its dramatic potential. This allowed the GST to shape a piece of street theatre around the kinds of questions people wanted to ask BHP Billiton’s chief executive (the retiring Don Argus), and thereby draw attention, on a ‘public stage’ as it were, to the environmental consequences normally glossed over by both the company and an often compliant or disinterested media.13

The environmental impact of BHP’s activities world-wide was analyzed and potential questions workshopped by GST members as the beginning of a rudimentary ‘text’ (matrix) for the performance. This involved researching the mining industry generally, and uranium extraction in particular, so that eventually the issues to be dealt with could be organised thematically under headings like: ‘Toxic Dust’, ‘Yellowcake,’ ‘Water Pollution,’ ‘Global Warming,’ ‘Legal Issues,’ ‘Effects on Indigenous Populations,’ ‘Industrial Relations,’ ‘Health and Safety,’ ‘Nuclear Proliferation,’ and ‘Personal Issues (relating to chairman Don Argus’s imminent retirement) etc.14

It was resolved that each ‘journalist’ would take a set of questions relating to one of these themes and fire them at the hapless ‘Sir Don’ in random order, much like real journalists with their own agendas. As a rudimentary ‘script’ developed, characters within the ‘Ratpack’ were designated as the ‘Nuclear Proliferation’ Journo the ‘Yellowcake’ Journo, the ‘Legal’ Journo, the ‘Water’ Journo, ‘Indigenous Affairs’ Journo, ‘Personal’ journo and so on. Meanwhile, ‘Sir Don,’ in the time honoured tradition of such events, would give a set of standardised, fairly meaningless, bland and ineffectual replies – literally dodging questions as he worked his way up towards the entrance to the Convention Centre while maintaining the illusion that he was in fact the chairman of this vast multi-national en route to its AGM. Such a tactic allowed Mike Russo and Scott Davis (playing Sir Don and his minder) to lead the Ratpack virtually all over the steps, as the impromptu ‘press conference’ went where ever it felt like. In this way, Mullumbimby’s GST physically plotted to get its message across to any interested shareholders arriving for the meeting and perhaps even to draw in the real media inevitably present at such nationally significant events and thus scoring points in the even greater contest for ‘space’ on the evening news.

Applying Lefebvre’s theory about the production of space, the area around the roving press conference is thus ‘vectored’ into being by the focus (energy) that multiple cameras and other recorders produce when pointed towards the same place (the interviewee). Another way of expressing this is to argue that energy itself originates with the interaction of polar opposites (points of alternate ordering). To invoke again the metaphor of Physics, electricity, for example, is created by an interchange between positive and negative terminals (direct current) or spinning magnets (alternating current). The polar opposites involved in a meta/physical confrontation, such as GST’s ‘press conference,’ are the antagonists themselves (Ratpack v. Sir Don). In this adversarial posture, lies the ‘charge’ required to ‘detonate’ performative space into being. All fights whether choreographed or impromptu (matrixed or non-matrixed) are also a kind of performance, with narrative through-lines, moments of tension, physical engagement, and sweaty endings. Even colloquial military parlance, the language of professional combatants, speaks of a “theatre of operations.”

Pearson and Shanks outline the basic spatial patterning at work here.

As a fight breaks out the crowd parts, steps back, withdraws to give the action space. Instantly they take up the best position for watching, a circle. It’s democratic, everyone is equidistant from the centre, no privileged viewpoints. There may be a struggle to see better but the circle can expand to accommodate those who rush to see what’s happening. Or it thickens. A proto-playing area is created, with an inside and outside, constantly redefined by the activity of the combatants, who remain three dimensional…The size and ambiance of the space are conditioning factors. Then just as quickly the incident ends, the space is inundated by the crowd and there are no clues what to watch. 15

Such a description could equally describe the modus operandi of the door stop press conference and a lot of what takes place in Sir Don.

Performing Sir Don v. The Ratpack

After 15 seconds of opening credits on the YouTube video,16 the performance of Sir Don v. The Ratpack is inaugurated at the 18 second mark with the line, “There he is!”. This is shouted out by the ‘Personal’ Journo as a predetermined cue to other GST ‘Journos’ to move towards ‘Sir Don’ and his minder just arriving around the corner of the Convention Centre (at the foot of the steps). As Dwight Steward advises, writing about political street theatre in the 1970s, “[h]ave an elastic beginning for your script, allowing time for a crowd to gather.”17 Clearly, the GST budget did not stretch to the provision of a limousine for Sir Don’s arrival moment and anything less would have undermined the all important element of authenticity. Consequently, this opening line was designed as the trigger point for other ‘Journos’ who just happened to be milling around nearby in small, discrete groups. Such an ‘invisible theatre’ tactic also allowed the GST actors to remain initially distinct and separate from the International Convergence, which was kept well behind police lines in the background. If GST’s performance of Sir Don had originated from within this larger, real demonstration it is doubtful that it would ever have made it to the intended starting point at the bottom of the steps. In this sense, the heterotopia of Sir Don was able to carve out its own spatial niche separate from the other, larger events taking place (the heterotopia of the real demonstration and that of the AGM). Thus the constructed space of the mock press conference starts to gather shape out of the ‘energy’ of the oppositional performances brought into being on the footpath.

Within a few more seconds the first questions about Sir Don’s imminent retirement are fired by the ‘Personal’ Journo and the video cuts to a high shot looking down (22 second mark).

(photo Paul Davies)

FIGURE 1. Polarising performative space into being

Members of GST’s ‘Ratpack’ confront ‘Sir Don’ effectively forming a circle around him.

A giant white elephant from the ‘real’ demonstration can be seen in the background (top right).18

Figure 1 shows the ‘Ratpack’ forming as a circle around the be-suited Sir Don and the minder to his immediate left: the ‘Ghost of Peter Garrett’.19 This uncanny player is also an archetypal accompaniment to the cult of celebrity: the private ‘body’ guard. Everybody present seemed to read and accept ‘Peter Garrett’s’ iconic role immediately, including the police and other security personnel, none of whom questioned the legitimacy of this character’s silent but intimidating presence: a composite of sunglasses, tightly held briefcase and small earphone – apparently connecting him to some larger, over-arching panoptic space of surveillance. Like any theatrical performance, props and costumes in site-specific practice are just as critical to the definition of character, perhaps even more so given the opportunities for more intense actor/audience relations and the need to maintain authenticity at such a close proximity.

As the ‘press conference’ makes its way up the steps it very quickly starts to draw in players outside the GST troupe including BHP officials, glimpsed in a somewhat flummoxed state in the background (and no doubt wondering who this important person is). Indeed, at the 30 to 40 second mark a man in a light coloured coat, possibly connected to BHP and clearly concerned that this VIP has been unintentionally accosted by a rabble-like press contingent, seems to be voluntarily attaching himself to ‘Sir Don’s’ security detail.

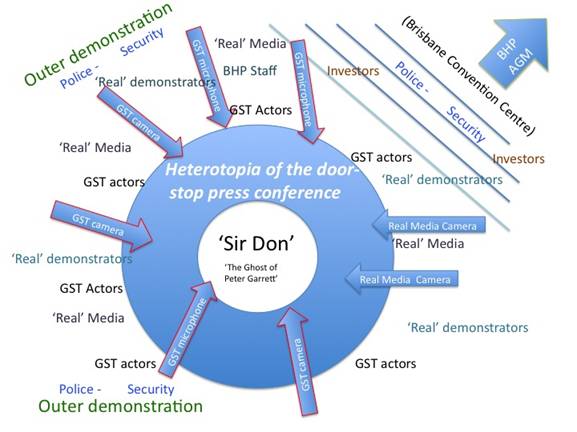

FIGURE 2. A map of the performative geography of Sir Don v. The Ratpack

The heterotopia of a mock press conference is maintained…but not contained by the vectored energy of cameras, sound recorders and questions.

Figure 2 shows how performance space is created in Sir Don using cameras and microphones which focus the outer edges of the circle towards the centre. In this way the arena of the press conference, with Sir Don marking its centre point, is given precedence over other spaces (such as the real demonstration nearby, and the AGM inside the Convention Centre). However, the journey of Sir Don v The Ratpack as a piece of agit-prop is precisely to move from the realm of the real demonstration into the alternately ordered space of the AGM, demonstrating Foucault’s point about the permeability of heterotopia.20

At 1 minute 30 seconds into the video record other participants in the demonstration, ‘real demonstrators’, apparently ignorant of the nature of the constructed ‘performance’ occurring here, as Boal predicts are also drawn into the ‘press conference,’ including an indigenous activist immediately behind Sir Don. After questions about the water supply for Roxby Downs (1 minute 40 seconds), dubious practices involving the military in West Papua working on behalf of BHP (2 minutes 30 seconds), carbon neutrality (3 minutes), BHP’s toxic legacy (3 minutes 30 seconds) and nuclear proliferation, the subject turns to yellow cake – a refined form of uranium ore. By now the ‘democratic’ circle encasing Sir Don has grown considerably as it moves around the steps picking up security people and real demonstrators like a rogue black hole, forming an unbroken (but permeable) loop around him. At the 4 minute mark, Sir Don makes a weak joke about how he “wouldn’t mind some yellow cake with his morning tea” since he’s “feeling a bit peckish” and draws a suitably disgusted response from some of the genuine activists present.21

At the 4 minute 30 second mark, one of these ‘real demonstrators,’ whether aware of the larger pretence or not (and in either case keen to take his place on a ‘stage’ created by GST) starts throwing in his own questions, asking about environmental destruction and social dislocation with the knowledge and conviction of a well informed activist. At this point all three social spaces present around the Convention Centre: GST performers, real demonstrators, and attendees at the AGM are now sharing the same frame. The collision of heterotopia is complete as the larger, real demonstration co-opts GST’s performative space and together they take on a spatial trajectory of their own.

As this roiling intercalation of separate representational spaces with their alternative agendas and viewpoints, now moves randomly towards the doors of Brisbane’s Convention Centre, like Pearson and Shank’s democratic circle round a fight, the shape of the press pack expands and contracts, elongates into an ellipse then spreads lengthways up the steps as journalists and onlookers jockey for a better view or greater access to questioning – shape shifting but maintaining the integrity of the performance space by always focusing on ‘Sir Don.’ By the 5 minute 20 second point ‘Sir Don’ (no doubt surprised that he had managed to get this far), calls to his minder and together they step blithely through the police line guarding the front doors into the space of the official AGM. By this stage most of the real demonstrators have peeled off assuming, not unreasonably, that their entrance would be blocked. Meanwhile the constructed space of GST’s performance piece, having gone through this crucial, literal portal, now superimposes itself (collides) into its oppositional place of ordering: the foyer area of BHP Billiton’s AGM. Although the ranks of the ‘Ratpack’ are now thinning, a determined few maintain a hot pursuit, their private, internal anxieties about getting this far no doubt reflected in the very nervous question framed by the ‘Radiation/Health’ Journo at 5 minutes 40 seconds.

Questions about the health of BHP’s workers continue as the mock press conference hovers under signs welcoming shareholders into the meeting and visually trumpeting the company’s many achievements. Clearly, by this stage, GST’s constructed heterotopia, having reached the liminal space on the edge of the private meeting, has gone about as far as it can and matters reach a climax as the questions turn to ‘Sir Don’s’ own health. This was the designated trigger question to ‘dramatically’ end the performance. At six minutes 30 seconds, as he tries to answer, Sir Don appears to suffer some kind of breathing difficulty, and asking for water, soon collapses to the ground, causing another layer of confusion (7 minutes) as real doctors (including anti-nuclear activist Dr. Helen Caldicott – present an investor/protestor) start discussing the need to call an ambulance (Figure 3).

(photo Paul Davies)

FIGURE 3. Denouement

Sir Don ‘collapses’ inside the space of the AGM and is attended by doctor-shareholders

At this point the Happening comes to an oddly anti-climactic denouement as ‘Sir Don’, (doubtless sensing the problems that could flow from a real ambulance being called), miraculously recovers, gets to his feet, and calmly walks back out of the building through its glass doors. Again, as Pearson and Shanks predict, the spectatorship gathered around a fight can just as effortlessly fade away, as happens here. “The incident ends, the space is inundated by the crowd and there are no clues what to watch”.22 Hence the space of the Happening can evaporate just as readily as it can form.

In truth, nobody in Mullumbimby’s GST imagined the ruse would work to the extent that ‘Sir Don’ (and the combined Ratpack) would be able to simply walk past a police line and enter the foyer of the building where the audience for BHP’s AGM was already gathering. This second order of spectators, now drawn inevitably into GST’s invasion of their space, consisted of small investor/shareholders, fund managers, corporate staff, police and security personnel. There was clearly risk involved at this point in needlessly engaging real emergency services, such as an ambulance. TheatreWorks’ location plays also demonstrated that when fictional elements are inserted into real locations and commonly recognised social situations, unexpected consequences can flow. Fortunately, the performance of Sir Don ended before anything untoward occurred. In this case, Steward’s warning about having a definitive conclusion to a street theatre performance clearly applies.23 The collision of created spaces (mock press conference into AGM) becomes fraught as a result of the intervention of real people (doctors in fact) confronting, from their point of view, a real (medical) problem.

Having previously only glimpsed critical need for a definitive conclusion, I recall suggesting in the workshops, that ‘Sir Don’ should have a penultimate light-bulb moment when the torrent of questions about the damage done by his company would see him undergo a ‘road-to-Damascus’ moment and admit to the error of his ways – precipitating some kind of personal crisis. And although Sir Don’s collapse was taken seriously by those present who were not party to the pretence, this sort of narrative conclusion seemed rather ‘in-authentic’ and fairly unlikely, given both the character involved and the context (and it was). Thus, GST’s management of the space of its mock press conference worked to expectations in terms of the questioning and the drawing in of other demonstrators, media, investors, staff and security, but it failed Steward’s important test of providing a convincing or satisfactory exit from the scene.

Towards a site-specific, critical toolkit.

This raises the question of how Sir Don v. The Ratpack measures up in terms of a set of assessment criteria that might inform and guide future site-specific work. This list is meant to be more descriptive than prescriptive, and again derives from the broader investigation into what did and didn’t work in TheatreWorks’ location plays.

Authenticity (Spatial Relations).

That the performance had an aura of authenticity is reinforced by the ease with which onlookers and other players were so readily drawn in to the ruse. Even a dress rehearsal in nearby St. Mary’s Catholic Church car park immediately before the performance drew in an audience of passers-by. Obviously, a door stop press conference involving some important person in a suit is entirely to be expected around the fringes of events like the Annual General Meeting of a major corporation. All the props, cameras and recorders, were genuine and some were working (hence the YouTube video). As the action proceeds the space of the real demonstration blends into the space of the mock conference, which in turn moves into the foyer of the Convention Centre and mingles with the periphery of the AGM. All three major spaces of contention therefore have porous borders. The problem identified in relation to ending the performance occurs inside the Convention Centre’s foyer where the invented space of the mock door stop essentially fizzles out for lack of narrative content (i.e. contest/questions). However, in the wake of the performance a number of television networks did refer to the event on their evening bulletins and articles mentioning it appeared in at least two newspapers.24

Complicity (Audience Relations).

Some onlookers remain passive (one suspects they were mostly investors or neutral by-standers), others – obviously more politically committed – became quite active as they begin to throw in their own questions. In some cases they also become quite angry with Sir Don’s flippant responses.

The performance clearly transgresses a police line designed to protect BHP’s AGM from any attempt at disruption. In this sense the mock press conference and its various hangers-on, becomes complicit in a strategy to occupy a space they were officially and legally prohibited from.

Mobility.

Above all mobility was the most important element in the conception and execution of Sir Don. The constant moving about of journalists and subject, the hankering, restless, nervous deployment of cameras and microphones, the urgency of the questions (time is money), all mimicked what happens in a real, door-stop press conference. These temporary media events are expected to move and this adds to the performance a measure of credibility, urgency, danger and unpredictability.

Sensibility.

No other senses appear to have been involved apart from sight and hearing, although a certain amount of jockeying for position (haptic space) was involved in the constitution of the media ring, with various ‘journalists’ jostling each other for optimal viewing and interrogating space. Whether such close contact introduced the pheromone effect (olfactory space) is unclear from the video record.

Synchronicity.

Consistent with most site-specific productions, the action unfolds in real time and lasted for approximately 15 to 20 minutes in total. The video record is therefore an edited version containing about half the total exchange of dialogue and action that took place. This length surprised the GST participants since in most rehearsals, the improvised questioning on various Mullumbimby staircases rarely ran to more than 5 minutes.

Conclusion

With the exception of the unresolved, potentially risky and odd ending, Sir Don v The Ratpack, satisfies most of the above criteria required for a reasonably successful ‘site-specific Happening’. Its usefulness as a example of agit-prop street theatre was recognised at least by the editors of GST’s hometown newspaper The Byron Shire Echo, who described it as “one of the most effective and entertaining forms of protest.”25

Clearly the ‘heterotopia’ of a performative space, can be created through the focused energy of a semi-improvised performance. The challenge lies in managing that space once it has been ‘produced’. This involves not only elastic beginnings and definitive endings, it also brings into play the relationship between a performance space and all the spaces, imagined or real, that surround it. The permeability of all these different areas ensures that collisions and exchanges (of energy, people, narratives) is almost certain to take place. Such a spatial frisson gives site-specific performance both its unique potential and its most serious limitation: the potential risk involved when reality confronts fiction. Controlling such risk throughout the intercalations and superimpositions that occur when a play is produced on location is perhaps the most important criteria for successful (pain free) spatial management. And if public liability requirements are to demarcate an official limit to some forms of site-specific practice, then containment of that risk becomes even more crucial. Otherwise theatre practice loses the chance to produce ever more fertile arenas in which to explore actor/audience relations and whole new ways of experiencing stories in places so ubiquitous and available.

NOTES

- An 8 minute video record is viewable online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDD1q_sjor0 . Viewed 14 May 2012.

- Boal describes ‘Invisible Theatre’ as “rehearsing a scene with actions that the protagonist would like to try out in real life, and improvising it in a place where these events could really happen, in front of an audience who, unaware that they are an audience, accordingly act as if the improvised scene was real.” The Rainbow of Desire, the Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy (London: Routledge, 1995) 184.

- Henri Lefebvre, La Production de L'Espace. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991) 13.

- Production de L'Espace 39.

- Michel Foucault ‘Of Other Spaces’. Trans. Jay Miskowiec. Diacritics 16 Spring (1986): 24.

- Kevin Hetherington, Expressions of Identity: Space, Performance, Politics (London: Sage, 1998) 128.

- Expressions of Identity 132; emphasis added.

- Expressions of Identity 131.

- Kevin Hetherington, The Badlands of Modernity: Heterotopia and Social Ordering (London: Routledge, 1997) 42.

- Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Rendall, S. (London, University of California Press, 1988) 117.

- That is to say not part of any “information structure.” See Kirby’s Happenings, quoted in note 1.

- Mike Pearson, Michael Shanks. Theatre/Archaeology (London: Routledge, 2001) 21.

- As Queensland’s disgraced former premier, Sir Joh Bejlke-Peterson famously boasted, attending a press conference for him was like “feeding the chooks,” a not-so-covert reference perhaps to its acknowledged disinformative function.

- Some of this background material included pamphlets like: Friends of the Earth’s BHP Billiton Alternative Annual Report: Undermining the Future (n. pub., 2009).

- Theatre/Archaeology 21.

- This opening sequence was not generated by GST directly. Instead it includes footage of the evacuation of a nearby office building – part of a fire-drill – that just happened to occur immediately after the live performance of Sir Don a few blocks away.

- Dwight Steward, Stage Left (Dover, Delaware: The Tanager Press, 1970) 21.

- Traditional street theatre tactics also employed large, hard-to-ignore puppets to make concise political points.

- Peter Garrett was Federal Minister for the Environment at this time and in his previous career as a rock musician had famously produced many political and environmental protest songs of his own.

- ‘Of Other Spaces’ 26.

- Indeed, as soon as the circle of the press conference began forming on the footpath there were loud “boos” directed at ‘Sir Don’ and GST’s Ratpack. Clearly, from the point of view of the ‘real demonstration,’ both the Media and BHP personnel were perceived to embody two halves of the same problem.

- Theatre/Archaeology 21.

- Stage Left 24.

- Tony Grant-Taylor, ‘BHP Predicts Strong Demand for Coal Sales’, Courier Mail (27 November 2009): 78 and Paul Davies, ‘BHP Billiton Hit by Gorilla attack’, The Byron Shire Echo (1 December 2009): 17

- ‘Backlash’, The Byron Shire Echo (1 December 2009): 68.